This exhibition presents the 30-year history of the Finnish Border Guard’s special intervention units.

Today, the Border Guard has two special forces units comprised of professional border guards. The 1st Special Intervention Unit operates under the Southeast Finland Border Guard District, while the 5th Special Intervention Unit operates under the Gulf of Finland Coast Guard District.

Special response teams have been trained and equipped to deal with the Border Guard’s most challenging border security tasks across the whole territory of Finland. In addition, special intervention units can also be used to support other authorities.

(By approving all cookies, you enable the embedded Youtube videos on the site. Captions are available on the videos in English, Finnish and Swedish. To turn on captions, click the “C” icon.)

1. The collapse of the Soviet Union transforms the security environment

During the years of the Cold War, the borders of Finland's eastern neighbour, the Soviet Union, were completely sealed off, and by the early 1990s Finland had become accustomed to the fact that the border situation would remain stable thanks to the USSR’s strict and effective border control.

This situation was then transformed by the collapse of the Soviet Union at the end of 1991 and the end of the Cold War. In Finland, the authorities watched with concern, worried that the collapsing superpower's border control would also disintegrate. A new threat that emerged was the possibility of a civil war in Russia, the heir to the Soviet Union, and resulting potential for uncontrolled immigration to Finland as people flee war and famine.

In autumn 1991, the government granted the Border Guard an appropriation of 30 million Finnish marks to improve border security. This political decision was the impetus for the formation of the special intervention units.

Pictures 1 & 2.

2. The special intervention units are established on 1 February 1992

In February 1992, the Border Guard set up a special division to be utilised for particularly demanding border security functions. This special division was intended to be a national border guard reserve force under the command of the Finnish Border Guard. The division was prepared for use either as a whole or divided into different teams under the direct command of each border guard district.

During 1992, the first divisional command and team-specific training plans were drawn up at the Finnish Border Guard College in Immola. The aim was to create basic capabilities for situations and threat scenarios in which the special division would have to be deployed.

The special intervention units were set up on the quiet, and after the selection of the team leaders for the various border guard districts, the supervisors indicated which border guards they considered suitable for the new special intervention units. Since 1995, there has been a basic special intervention unit course to which border guards have been able to voluntarily apply. The topics taught on the course include the personal skills and tools of an operator, the basics of special intervention unit tactics, and military defence skills.

Successful completion of this course is a prerequisite for being assigned to special response duties. Border guards that complete the course are also eligible to serve in other special roles, including as a Border Guard security guard or chauffeur, and to carry special weapons for official duties.

Until the 2000s, border guards who had been assigned to or applied for special intervention units still worked, as a rule, at their own border guard station in their own border control and border check functions. They therefore served in the special intervention units alongside their normal work. Today, however, serving in the Finnish Border Guard’s special forces is a full-time role.

Video 1. Border Guard Master Sergeant (ret.) Mika Albertsson explains how he ended up in the special intervention unit of the South-eastern Finland Border Guard District in the early 1990s. Albertsson served in the special intervention unit until 1997.

Pictures 3 & 4.

3. Special response team duties

At the beginning of the 1990s, the tasks of the special intervention units were defined as follows:

- Rapid establishment of a border control focus in a threatened area or rapid reinforcing and strengthening of border traffic control at border crossing points

- Supporting priority border guard districts to prevent large-scale illegal entry

- Supporting border guards in particularly dangerous border events involving armed activities or threats of such

- Assisting the police and other authorities

Each Border Guard District and Coast Guard District formed a special intervention unit. The teams consisted of a team leader, a deputy leader, a command team and three groups. In addition, each team was assigned two dog handlers, together with their dogs, and two divers were placed in the teams for coast guard districts. In the 2000s, special intervention unit operations were centralised within the 1st Special Intervention Unit of the Southeast Finland Border Guard District and the 5th Special Intervention Unit of the Gulf of Finland Coast Guard District.

During the start-up phase and special intervention units’ first years of operation, the teams mainly developed independently their own methods and tactics, with the main focus of their duties being on crowd management, riot control, and prevention of large-scale illegal entry. In Finland, operational and educational cooperation was and still is carried out with other authorities, such as the police and the Finnish Defence Forces.

Pictures 5−7.

4. Communications and public image

The headquarters of the Border Guard issued instructions that the media and the general public should not be actively informed about the newly established special intervention units. In the early years of special forces operations, a certain mystery shrouded the teams’ activities, and the special intervention units were considered by the media as some sort of ‘Border Rambos’. A variety of information has nevertheless been published over the years on the activities of the teams, but this has been done without compromising the operational activities of the teams and the occupational safety of their members.

Video 2. Excerpt from the Finnish Broadcasting Company’s current affairs programmes ‘Raja railona’ (Border breach), from autumn 1995.

Picture 8.

5. Equipment and transport vehicles

When the special intervention units were established, they mostly used the Border Guard's normal weapons and equipment, such as assault rifles and service pistols. Their range of weapons began to be developed, however, as they gained experience. This process has continued right up to the present day.

Managing the use of special weapons is an integral part of special intervention unit operations. The special intervention units also contain members who have received sniper training.

In the early years, the special intervention units’ mission-specific equipment consisted of riot control and assault equipment. As their experience has grown, their equipment has been actively developed by the teams themselves to better meet tactical requirements.

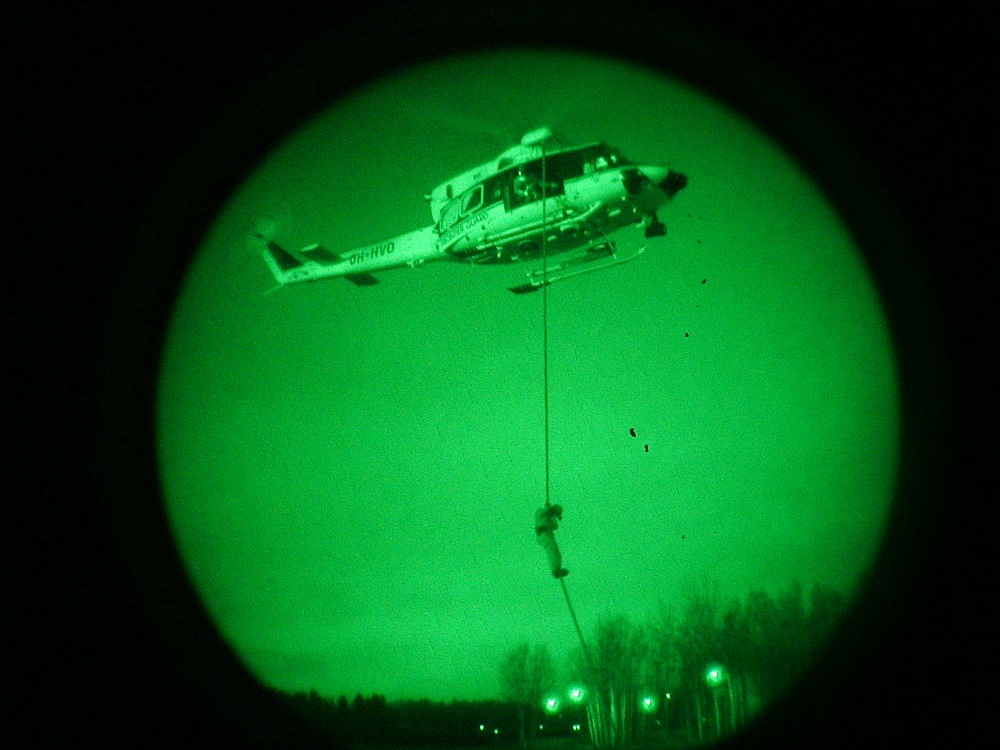

The Border Guard’s helicopters can be used for rapid deployment of special intervention units to mission areas. Air transport can also serve the needs of other authorities, such as the police. Depending on the task, the teams can make use of either the border guard districts’ off-road cars or rental cars obtained from elsewhere.

Border guards serving on special intervention units are also trained to operate in maritime environments. In particular, coast guard speedboats are used in transfer method training. The 5th Special Intervention Unit, which operates under the Gulf of Finland Coast Guard District, is the team that now specialises in maritime operations.

Pictures 9−13.

6. Large-scale exercise in Immola in May 1993

The special intervention units of all the Finnish Border Guard’s administrative units were assembled in May 1993 in Immola for the first large-scale exercise for the districts of south-eastern Finland. The Border Guard’s entire helicopter fleet also participated in the exercise. The exercise dealt with the scenario of large-scale illegal immigration from Russia to Finland. The exercise tested the technology, tactics and competence level of the special intervention units.

Lt-Gen (ret.) Jaakko Kaukanen recalls Ilkka Laitinen, who served as the leader of the Lapland Border Guard District's special intervention unit in the early 1990s and as Chief of the Finnish Border Guard in 2018–2019:

“South Karelia was struck that May by a heat wave that came from the Karelian Isthmus, so the temperature was already over 20 degrees. The team called in from Lapland, however, was equipped for Muonio's weather conditions. The stiff-legged boys from Lapland jumped out of a Super Puma in felt boots and fur hats, which amused those waiting to receive them."

"Ilkka was happy to report the team for duty. The warm clothing came in useful, however. The following night, the temperature even dropped below freezing. I met Ilkka that night at his little command post, grinning under his fur hat, right near the border by the village of Keskisaari.”

Video 3. Large-scale exercise in Immola in May 1993.

Video 4. Mika Albertsson recalls his participation in the Immola exercise.

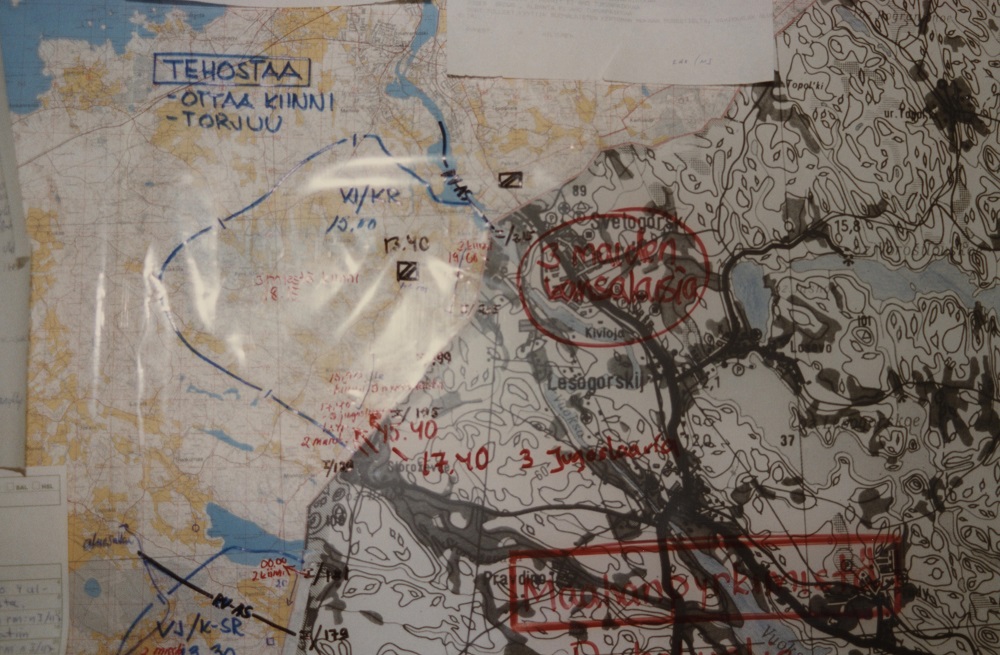

Pictures 14 & 15.

7. From exercises to real tasks

Video 5. Mika Albertsson explains how the environmental organisation Bellona tried to prevent the movement of a train carrying nuclear waste from Finland to Russia at Vainikkala railway yard.

8. Russian military defectors in the 1990s and early 2000s

In the 1990s and the early 2000s, one significant factor that weakened Finland’s border security was the illegal crossing of Russian military defectors from Russia to Finland. At that time, the Russian border guard service used conscripts for border guard duties. The conscripts suffered from bullying and poor conditions of service. The situations became dangerous at times, as the fugitives were usually carrying their service weapons.

Due to defection incidents from the mid-1990s onwards, the special intervention units operating on the Border Guard’s eastern border also began to take into account this prevailing threat in their own training.

Video 6. The Southeast Finland Border Guard District’s Special Intervention Unit practices apprehended military defectors in the Parikkala region in the late 1990s.

Video 7. Border Guard Master Sergeant Harri Ylä-Kotola, who served in the 1st Special Intervention Unit from 1995 to 2004 and from 2007 to 2016, recalls how there was talk at the beginning of the 21st century of disbanding the special intervention units as unnecessary.

Picture 16.

9. The tragedy of Sergei Strochihin

The 18-year-old Russian conscript Sergei Strochihin was the victim of severe bullying in his home garrison. On the evening of 24 May 2001, the desperate young man had abandoned his task of inspecting a freight train at Buslovskaya railway station and fled on the train to Vainikkala, on the Finnish side of the border. He took with him his assault rifle and two full magazines. From Vainikkala station, he headed to Vainikkala village, where he broke into an elderly couple’s apartment. Strochihin searched the house for food and cigarettes. The couple were taken hostage, but the husband helped his wife to escape through a window. He also succeeded in locking the fugitive in an upstairs room until help could arrive.

The Lappeenranta police took on the task of searching for and apprehending the fugitive, but due to limited resources, they asked for assistance from the Border Guard. The task was assigned to the special intervention unit of the Southeast Finland Border Guard District. In addition, border patrols were assigned to the search. On the morning of May 25, the house was found to be empty. A little later, the police were informed that a person using an automatic weapon had broken into Lauritsala's Neste service station. Strochihin had stolen food from the gas station as well as a car from a nearby village.

The search focused on the city of Lappeenranta and on Highway 6. A Border Guard helicopter was sent to the scene and also participated in the search. Strochihin fled towards Helsinki, driving at high speed along Highway 6. The fugitive recklessly overtook other traffic, endangering the lives of many. In Toikkala, Luumäki, his car collided with the trailer of a truck. The car, broken down the middle, tumbled off the side of the road. The fugitive somehow survived, however, and opened fire on the police car that arrived at the scene.

Video 8. A Border Guard helicopter chases along Highway 6 a car stolen by a Russian conscript.

A special intervention unit moved to Toikkala to protect the field command post established along Highway 6. The search continued with the help of a police dog, but no trace was found. The special intervention unit took over the task, and was given the following order authorising the use of force: ‘If the target individual is detected, their activity is to be halted with firearms.’ The border guards followed the trail with the dog for about a kilometre. In the end, they found Strochihin dead. He had committed suicide with his own service weapon.

Video 9. Harri Ylä-Kotola recalls the case.

Video 10. An operator, who served on the special intervention unit from 1999 to 2020 and is referred to as L 51, speaks about the case. He began his career as a normal member of the team, then served as the dog handler’s bodyguard and finally as group leader.

Colonel Jaakko Kaukanen, who was Commander of the Southeast Finland Border Guard District at the time, gave recognition to the professional work done by his troops. The events of May 2001 clearly demonstrated to all sceptics the need for special intervention units and put an end to talk of disbanding them. The cases of military defection came to an end, meanwhile, once the Russian border guard service stopped using conscripts for border guard duties.

Pictures 17−19.

10. Special response teams' dog operations

Video 11. Harri Ylä-Kotola talks of the use of dogs in special forces operations.

The Belgian sheepdog is a breed well suited to the operations of special intervention units. It is able to travel on boats and in helicopters. It is also suitable for tracing tasks and the use of force in marine environments. Dog handlers working in special intervention units have completed the Border and Coast Guard Academy's dog handler course and special intervention unit dog handler course.

Border guard dogs serving on special intervention units are an integral part of their own work community. When the dogs finish their service, the stories and memories of them live on. This was the case also with Remu. In one exercise, a rubber boat was inadvertently filled up so full that gasoline started flowing into the bottom of the boat. Remu, who was on board, got some of the stinging fuel on his backside. The unmuzzled dog was startled and, in a fit of anger, bit the hand of his nearby handler. Fortunately, Remu was still a puppy at the time of the incident, and his canines hadn’t yet come through. After that incident, Remu always wore a muzzle.

Pictures 20 and 21.

11. Casualties and losses

Although the special intervention units have not so far suffered any casualties in their operational tasks, one of the border guards who served in a special intervention unit was killed during an international crisis management mission. Petri Immonen, a junior border guard serving in the Southeast Finland Border Guard District Special Intervention Unit, was killed by a roadside bomb in Afghanistan on 23 May 2007.

Picture 22.

12. Special response teams are transformed into full-time special forces units

By the beginning of the 2000s, the special intervention units’ crowd management tasks, and the training for such tasks, began to decrease. The training instead began to emphasise search operations and catching dangerous persons. During the 2000s, the operators who had served in the special forces units began to work full-time as special forces operators.

Video 12. Operator L 51 speaks of the development of special forces operations.

Video 13. When operating in a marine environment, special intervention units may have to pursue fleeing persons or board vessels.

Picture 23.

13. Close cooperation between authorities in national-level special forces operations

With the establishment of the special intervention units, the need for tactical training of special forces was identified. In the early days, border guards jumped from a height of several metres from hovering helicopters. This led to bruising, twisted ankles and broken legs. Training in fast roping was initially provided by the Utti Jaeger Regiment. With the training received from the Defence Forces, the Border Guard began using fast roping with its own helicopter fleet.

Video 14. Nowadays special intervention units practice close co-operation with Finnish Defence Forces NH 90 helicopters. Also armoured personnel carries are used in operations and exercises.

In the 2000s, national special forces cooperation has been intensified between the 1st and 5th Border Guard special intervention units, the Utti Jaeger Regiment’s Special Jaeger Battalion, the Coastal Brigade’s Special Operations Detachment, and the Police Rapid Response Unit. In a small country like Finland, operators working in special forces know each other well and joint exercises are used to refine common practices and operating methods. Such cooperation also facilitates full-scale and smooth use of the capabilities of the different authorities.

Video 15. Special response teams have also been trained to operate in possible hostage situations, where necessary in cooperation with the police.

Video 16. Where the need arises, the Border Guard can provide executive assistance to other partnering authorities. Harri Ylä-Kotola recalls the 2009 Finland–Russia football match at the Helsinki Olympic Stadium, where the special intervention units supported the Helsinki Police Department.

Pictures 24 & 25.

14. International exercises and operations

The special intervention units have participated in several international special forces exercises. These have provided useful contacts with foreign special forces units, as well as a good opportunity to exchange perspectives and experience on special forces tactics. In addition, participation in international exercises is a good way to measure the skill and competence level of one's own group. Finland actively participates in the European Union’s ATLAS police cooperation network and participates in international special forces exercises organised by its member countries. Foreign partners that have worked closely with the Border Guard include the German federal police’s counter-terrorism unit GSG 9 and the Estonian police’s tactical unit K-kommando.

Video 17. International special forces exercise SEAL 2021 saw the participation of Finnish Border Guard Special Intervention Units and Police Rapid Response unit.

Video 18. In international operations, the special intervention unit operators have also been involved in saving lives. A story of searching for a missing old man in Greece.

Video 19. Harri Ylä-Kotola gives his views on participating in international operations.

In recent years, the Finnish Border Guard has been actively involved in operations at the EU’s external borders which are coordinated by the European Border and Coast Guard Agency Frontex. The idea is to promote European border management by working together to prevent illegal immigration flows and cross-border crime from entering the territory of the European Union.

Pictures 26 & 27.

15. Special forces identity

Service as an operator in a special forces unit can bring memorable experiences. Once an operator finishes their service on the team, it is very possible that their time there will have left a permanent mark on their professional and personal identity.

Special response teams were established 30 years ago as the Border Guard's reserve force for dealing with challenging border control situations. At the turn of the millennium, the usefulness of the teams was already being questioned, but the capacity of the teams for tackling special tasks has proved to be an important and needed resource. Special response teams trained for special forces operations are also able to operate effectively in the face of today’s hybrid threats, both in Finland and abroad.

Video 20. Three men who have served in special intervention units share their views on what their time in the team gave to them and what qualities are required for a good operator.

Picture 28.

Pictures

Chapter 1

Picture 1. Etelä-Saimaa, 24 February 1992.

Picture 2. Prime Minister Esko Aho and Minister of the Interior Mauri Pekkarinen with Chief of the Finnish Border Guard Lieutenant General Matti Autio in Nuijamaa.

Chapter 2

Picture 3. A special intervention unit riot response exercise in Immola in the 1990s.

Picture 4. Border Guard officers supervising and leading special intervention unit training exercises in the 1990s.

Chapter 3

Picture 5. Kainuu Border Guard District’s special intervention unit on an exercise in Inari.

Picture 6. Lieksa, May 1993. The North Karelia Border Guard District’s special intervention unit practice apprehending a person who has crossed the border illegally.

Picture 7. Special response border guards learning in 1993 about the road traffic control operations of the mobile police.

Chapter 4

Picture 8. Helsingin Sanomat, 4 September 1992.

Chapter 5

Picture 9. Special response team member firing an assault rifle.

Picture 10. Sniper training in the 1990s, using the Finnish sniper rifle 85.

Picture 11. Parikkala Special Intervention Unit members advancing in a building with their assault equipment.

Picture 12. North Karelia Border Guard District’s operators practising joint operations in the 1990s with one of the Border Guard’s AB 206 helicopters.

Picture 13. Coast guards practice handling a special response boat on the waters of Airisto in summer 1992. Image: The Coast Guard Museum.

Chapter 6

Picture 14. Situation picture at the Immola Exercise Command Centre of simulated illegal immigration into the Imatra region.

Picture 15. Captain Ilkka Laitinen (middle) leads the Lapland Border Guard District's special intervention unit.

Chapter 8

Picture 16. Etelä-Saimaa, 11 July 1995.

Chapter 9

Picture 17. Etelä-Saimaa, 26 May 2001.

Pictures 18 and 19. Letter of thanks from Colonel Jaakko Kaukanen, Commander of the Southeast Finland Border Guard District. Open the letter as PDF file (in Finnish).

Chapter 10

Picture 20. Remu, the border guard dog of the Gulf of Finland Coast Guard District’s 5th Special Intervention Unit, climbing aboard a vessel in autumn 2014 together with his handler ‘Ukki’.

Picture 21. Memorial service for Remu at the Gulf of Finland Coast Guard District in June 2017.

Chapter 11

Picture 22. Petri Immonen, a border guard who was killed during a peacekeeping mission in Afghanistan, is attended at his funeral by his fellow border guards.

Chapter 12

Picture 23. The 1st Special Intervention Unit practices apprehending a dangerous person in Pelkola in 2010.

Chapter 13

Picture 24. A special intervention unit practices fast roping from a Finnish Defence Forces Mi-8 helicopter in Utti.

Picture 25. Cooperation between the Border Guard, police and Finnish Defence Forces in a local defence exercise organised at the Helsinki Olympic Terminal in 2016.

Chapter 14

Picture 26. Operators from the Border Guard’s 5th Special Intervention Unit and the Police Rapid Response Unit at the SEAL 2021 exercise in the Baltic Sea.

Picture 27. The operators of the 5th Special Intervention Unit in the Mediterranean Sea in 2017.

Chapter 15

Picture 28. Operators who have served or are currently serving in the Border Guard's special intervention units carry on their chest a winged symbol which shows they belong to a special forces unit.